This last Christmas, when I visited my grandfather, I saw this game I had gifted him a few years ago. I asked him if he had solved it, and to my surprise, he hadn’t found a solution yet. I remember seeing his notes, the strategies he came up with (back-tracking, segmenting the regions), a gentle reminder of how interesting the game is. I personally had also only solved it once, and since I enjoy solving problems with programming, why not coding a solution for it?

The rules

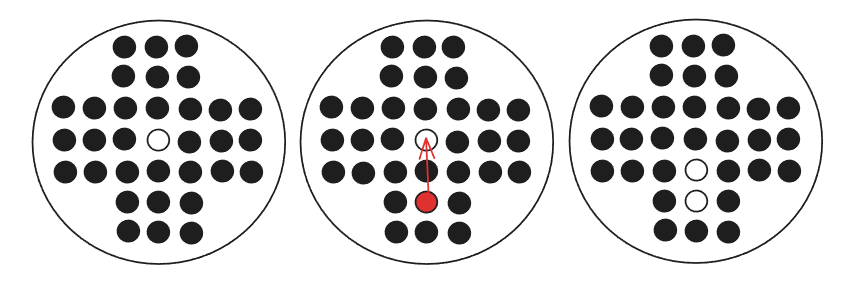

The rules are straightforward:

- You can jump over a single ball horizontally or vertically if there’s a free space available in the same direction of the jump

- You cannot jump diagonally

The goal is to end the game with a single ball on the board.

Solving it with code

Let’s define a bunch of classes to represent the game state:

Direction: will be used to calculate the next jumps from a given point:

enum class Direction(val x: Int, val y: Int) {

UP(0, -1),

LEFT(-1, 0),

RIGHT(1, 0),

DOWN(0, 1);

}

Point will correspond to a ball location:

data class Point(val x: Int, val y: Int) {

fun move(direction: Direction): Point {

return Point(x = x + direction.x, y = y + direction.y)

}

}

PointMovement will give us each move:

data class PointMovement(

val from: Point,

val to: Point

)

And finally, PegSolitairePointGrid will hold the information about the filled balls:

To solve this game, we can use DFS (Depth-first search) from the starting position and just traverse all possible moves. At any given position, we start a new path if we find a valid move. Eventually, there’ll be only ball remaining.

Now run that code and be surprised that it takes a while. On my laptop, around 75 seconds. So, let’s optimize it

Optimizing it

The first gain can be achieved by arranging the order of the points before the next traversal. Notice how we add the destination point whenever we jump, which moves our most recent position to the end of the point list. What this ends up doing is deprioritizing that specific point for the next traversal, which might not be ideal. Let’s see what happens when we prioritize the last point we moved to:

newPoints.add(dstPoint)

becomes:

newPoints.add(0, dstPoint)

And this ends up cutting the time from 75 seconds to mere 625 ms! Why does this happen? My assumption is that prioritizing the last move gives the algorithm a heuristic to stay closer to the region it’s currently cleaning. By playing around with the traversal order, I noticed if points get sorted by their y coordinate instead, it shrinks it down further to 300 ms!

newPoints.sortBy { point -> point.y }

This only applies to the first move being played down, as the remaining points are isolated at the top and sorting by y would prioritize that section to be cleaned up before proceeding to the next region. If you start with a different move other than that, you get different results. There’s a lot more of research that could be done for the best heuristic, but I didn’t want to go down that route.

Further optimizations

Another optimization I went with is decreasing the number of allocations to a minimum and storing the points in a sorted set. We can represent 2D points with just integers, where the most significant digits hold one coordinate and the less significant another. For this game, we need at most a 7x7 grid, which means 2 digits to represent a single point are enough.

Example: Point at y = 2, x = 1 and be modeled as the integer 21 instead of the concrete point object:

fun encodePoint(x: Int, y: Int): Int {

return (y * 10) + x

}

fun decodeX(point: Int): Int {

return point % 10

}

fun decodeY(point: Int): Int {

return point / 10

}

We can do the same for the moves, where 4 digits are used. The first 2 for the source point and the last 2 for the destination point:

fun createMovement(src: Int, dst: Int): Int {

return src * 100 + dst

}

fun extractMoveSource(move: Int): Int {

return move / 100

}

fun extractMoveDestination(move: Int): Int {

return move % 100

}

Now, to store in a sorted set, I went with TreeSet and the following comparator to sort by the y coordinate:

class YCoordinateComparator : Comparator<Int> {

override fun compare(o1: Int, o2: Int): Int {

val pointOneX = PegSolitaireCoordinates.decodeX(o1)

val pointOneY = PegSolitaireCoordinates.decodeY(o1)

val pointTwoX = PegSolitaireCoordinates.decodeX(o2)

val pointTwoY = PegSolitaireCoordinates.decodeY(o2)

val n1 = pointOneY + pointOneX * 10

val n2 = pointTwoY + pointTwoX * 10

return n1.compareTo(n2)

}

}

After using TreeSet and encoding points as integers instead of objects, the program now finishes in 15 ms!

To recap the optimizations so far:

- Plain DFS finishes in 75 seconds, blindly searching for solutions and deprioritizing the last move

- Prioritizing the last point brings the time down to around 625 ms

- Sorting points by their y coordinates brings time down to 300 ms

- Storing the points in a TreeSet of integers and minimizing allocations brings it down to 15 ms

How many solutions are there?

This question had my curiosity. Let’s define a solution as follows:

A sequence of moves from the initial position that leads to one ball remaining

It’s important to define it this way, because many “solutions” are symmetrical or seemingly identical. Notice how the initial position has 4 valid moves. For the purpose of this definition, all of those moves lead to different solutions since they move different balls.

The answer was surprisingly high to me: 81.723.294.080.159.936! See below to how I found this number.

Initial attempt

It might be tempting to adjust the DFS solution code to this instead:

if (filledPoints.size == 1) {

numberOfSolutions++

continue

}

And then just casually wait for 2.870.505 years, as this was generating around 3.250.000 solutions per hour on my laptop.

Finding identical boards

When a plain DFS is not enough, it usually means we need to cache results somehow. When traversing the different solutions, we can keep track of the boards we’ve seen already, since we might face them from different moves. To do that, we need to come up with a way of identifying each board uniquely. We can do that by generating, for example, a String containing all the currently filled points coordinates, such as:

000102

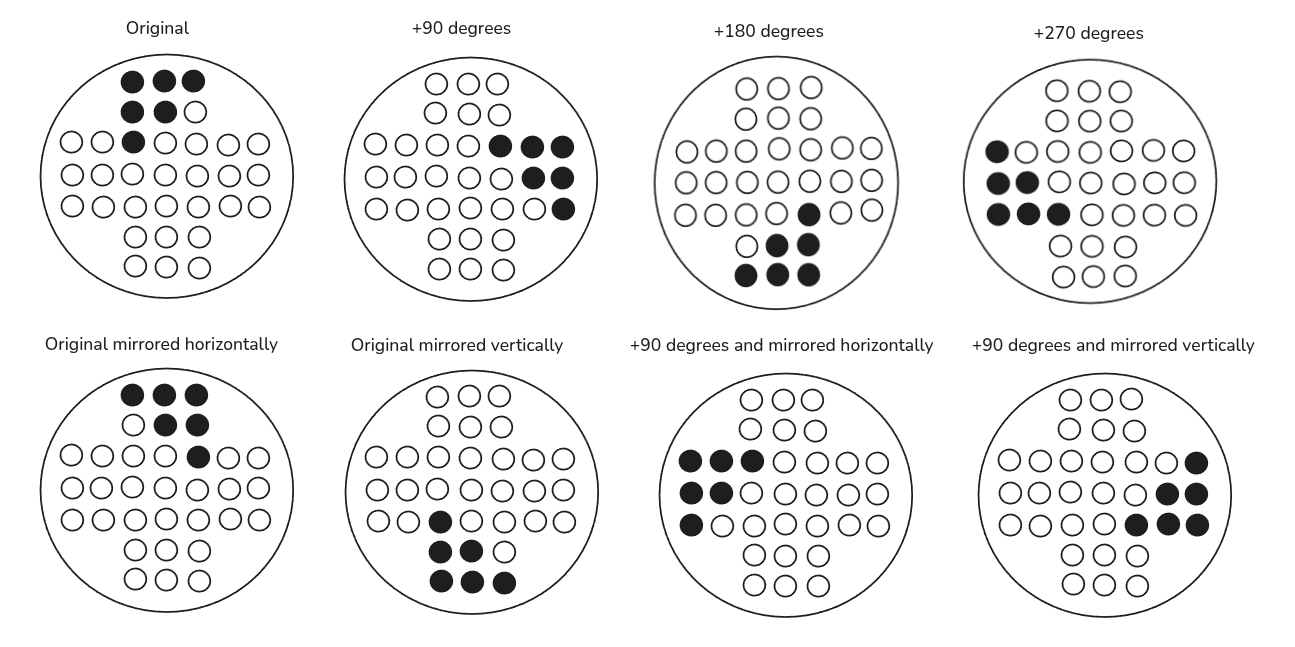

This would contain all points filled in the first row. This is enough to identify the boards, but what now? Like I mentioned before, there are symmetrical boards. If we’ve seen a symmetrical board, we can just re-use those pre-calculated solutions instead of going down their path again, which can be really long. How many identical boards are there?

This means that now we need to keep track of the visited boards, but at the same time check if we’ve visited a symmetrical board by generating the other 7 variants for each board we process. This will speed up the algorithm and everything will work, right?

Apparently not:

java.lang.OutOfMemoryError: Java heap space

Yet another data structure

So we optimized the execution time, but unfortunately we still need to cut memory to calculate all solutions.

This time, let’s represent the boards by using a 33 bit number! We have 33 positions, so we just need 33 bits to model the entire board.

We can use a Long and keep each bit pointing to an index of the board:

fun buildLongGrid(): PegSolitaireLongGrid {

val board = StringBuilder()

repeat(33) { index ->

// Center piece is empty

if (index == 16) {

board.append('0')

} else {

board.append('1')

}

}

return PegSolitaireLongGrid(board.toString().toLong(radix = 2))

}

The initial board is then:

11111111111111110111111111111111

This also means that we no longer need an extra id calculation, the board itself is the id!

@JvmInline

value class PegSolitaireLongGrid(

val id: Long

)

Finding if a position is filled is now done by shifting our desired index to the right and then just applying the AND operator with 1:

fun isFilled(index: Int): Boolean {

return (id shr (GRID_SIZE - 1 - index)) and 1L == 1L

}

Transforming the board with moves now doesn’t involve collection mutations as well. It’s now just a bunch of bit shift operations which are a lot less expensive than the previous code that was creating a copy of the original collection and mutating it.

if (isFilled(neighbourIndex) && !isFilled(dstIndex)) {

// Erase src point

var newGridId = id xor getIndexBit(index)

// Erase neighbour point

newGridId = newGridId xor getIndexBit(neighbourIndex)

// Add dst point

newGridId = newGridId or getIndexBit(dstIndex)

}

private fun getIndexBit(index: Int): Long {

return 1L shl (GRID_SIZE - 1 - index)

}

Now we can plug this for the final solution:

Here’s a small summary of the algorithm:

- Go through each board that is the result of moving one piece

- For the upcoming board, check if we’ve already seen it or one of its 7 other variants. If yes, return it’s pre-calculated solution. If not, continue searching for valid moves

- Add the number of solutions for the board we just created to the current board being processed

This function still takes around 2 minutes on my laptop, but hey, it’s better than waiting millions of years!

Conclusion

I ended up sharing these results with my grandfather, and he couldn’t honestly believe it, and I get it. I was surprised to see that such a difficult game to solve manually actually has a lot of valid solutions.

A simple DFS was enough to find a solution, but finding all of them required a complete rethink of data structures.

Now back to solving this game manually, and finding one of the 81.723.294.080.159.936 sequence of moves!